Morphea, also known as localized scleroderma, is a rare skin disorder that causes hard, thickened patches of skin. Unlike systemic scleroderma, which can affect internal organs, morphea is usually limited to the skin and sometimes the tissues just beneath it. Though the condition is not life-threatening, it can significantly affect a person’s physical appearance and quality of life depending on its severity and location.

What Is Morphea?

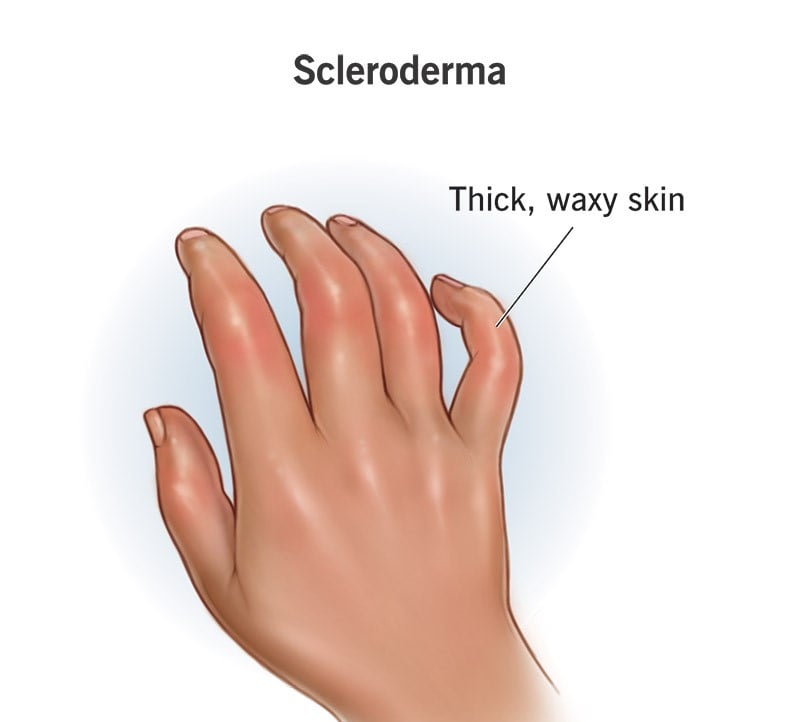

Morphea is a form of localized scleroderma, meaning it primarily affects specific areas of the skin and connective tissues, not the entire body. The name “scleroderma” means “hard skin,” which describes the main symptom of this condition skin that becomes stiff and thick due to excessive collagen production (Florez-Pollack et al., 2019). Collagen is a protein that helps keep skin firm and elastic, but when too much of it builds up, it leads to the formation of hard patches or plaques.

Morphea can appear in different forms, including:

- Plaque morphea – the most common type, where oval or round patches of hard skin develop.

- Linear morphea – usually occurs on arms or legs and may affect muscles or bones underneath.

- Generalized morphea – involves several patches spread across larger body areas.

- Pansclerotic morphea – a severe and rare type that can affect deeper tissues.

Causes and Risk Factors

The exact cause of morphea is not fully understood, but it is believed to be related to an autoimmune response. In autoimmune diseases, the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues. In morphea, this leads to inflammation and excessive collagen production in the skin (Peterson et al., 2019).

Some potential triggers or risk factors include:

- Genetics – a family history of autoimmune conditions may increase the risk.

- Infections – certain viral or bacterial infections might trigger an immune response.

- Radiation or trauma – physical injury or radiation exposure to the skin may contribute.

- Environmental factors – though less clear, environmental exposures might also play a role.

Morphea is more common in females than in males and typically appears between the ages of 2 and 14 in children or in the 30s and 40s in adults (Leitenberger et al., 2009).

Symptoms

The main symptom of morphea is the appearance of firm, discolored patches on the skin. These patches can be red, purple, or brown and may eventually become white or shiny as the skin hardens. Other symptoms include:

- Skin tightness or discomfort

- Reduced mobility if joints or muscles are affected

- Hair loss over the affected area

- Skin thinning or ulceration in severe cases

In linear or deeper forms, morphea can interfere with limb growth in children or cause disfigurement, especially when it affects the face or scalp.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing morphea usually involves a physical exam and a review of the patient’s medical history. A dermatologist may perform a skin biopsy, where a small sample of skin is removed and examined under a microscope. Imaging tests like MRI may be used in deeper or linear forms to assess underlying tissues (Florez-Pollack et al., 2019).

Treatment Options

There is no cure for morphea, but treatment can help control symptoms and prevent complications. The choice of treatment depends on the type, severity, and depth of the condition. Common treatments include:

- Topical corticosteroids – reduce inflammation in mild cases.

- Phototherapy – ultraviolet (UV) light therapy can help soften the skin and reduce inflammation.

- Immunosuppressive drugs – medications like methotrexate are used in more severe or rapidly progressing cases (Peterson et al., 2019).

- Moisturizers and physical therapy – help manage stiffness and dryness and maintain mobility.

Early treatment is important to prevent long-term damage, especially in children with linear morphea.

Living With Morphea

While morphea is not contagious or fatal, it can have a psychological impact, particularly in visible or disfiguring cases. Patients may experience anxiety, depression, or low self-esteem. Support from dermatologists, therapists, and patient support groups can be very helpful in managing the emotional side of the condition.

Education about the disease and consistent follow-up with healthcare providers are key in managing the disease long term. In some cases, morphea may go into remission or become inactive on its own after a few years, but ongoing care is often necessary to monitor for changes or relapses.

Morphea is a rare and often misunderstood skin disorder, but with early diagnosis and appropriate treatment, most people can manage it effectively. While the cause remains unclear, research continues to improve our understanding and treatment of this condition. Anyone noticing unusual skin changes should seek medical attention to rule out morphea or other skin diseases.

References

- Florez-Pollack, S., Kunzler, E., & Jacobe, H. T. (2019). Morphea: Current concepts. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology, 12, 697–704. https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S178897

- Leitenberger, J. J., Cayce, R. L., & Haley, R. W. (2009). Distinct autoimmune syndromes in morphea: A review of 245 adult and pediatric cases. Archives of Dermatology, 145(5), 545–550. https://doi.org/10.1001/archdermatol.2009.56

- Peterson, L. S., Nelson, A. M., Su, W. P., & Mason, T. (2019). Classification of morphea (localized scleroderma). Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 70(11), 1068–1076. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-6196(11)64484-3